I remember having what several leading psychologists might call a "holy shit" moment when I first saw Anna Webber's band play, shortly after I moved to New York. Her music is smartly crafted and complex without feeling stilted or stodgy. It manages to be both visceral and cerebral; it's surprising without sacrificing compositional unity. You can hear a wide range of influences in her writing and playing, and yet you can't say that there's anyone else out there right now making music that sounds like this.

Her new record is called "Simple" and it's been out for about two months. It features two other incredible players, Matt Mitchell (piano) and John Hollenbeck (drums), and it's been receiving great reviews. You can pick up a copy here.

I interviewed Anna a few months before the CD's release; we talked about some of her compositional strategies, morse code, the NYC jazz scene, and writing for a big band. Read; listen; enjoy.

Will Mason: What are some of the things you do to sketch out your pieces? Do you write at the saxophone, or piano, or pencil and paper?

Anna Webber: I have a notebook where I keep all sorts of ideas. I tend to gravitate towards formal ideas, but these can also be melodic or rhythmic, or whatever else. I try to keep it to small cells. So generally when I start composing I just grab my notebook and see if there's anything that interests me that I haven’t done. I don’t have a piano at home, just a midi-controller keyboard. I’m also not much of a pianist, I find it a little more of a hindrance. A lot of people seem to improvise at the piano when they’re starting to write; if I did that, I’d probably just play some D-sus chord over and over. Maybe all of my pieces would just be D-sus all the time... But that said, I try to use all the things that I can — flute, saxophone, singing something.

There’s this modular way of composing that you just described and, having seen your scores, I think this is visually present in your scores but completely not audible — everything seems so seamless. It’s one of the interesting things about your music, and it reminds me of Tim Berne, who also seems to me to structure music in this modular sense but in a way that yields a fluid and seamless result. When you compose, how much are you thinking about how these things are going to end up combining together into one 10-15 minute song?

I try and develop everything from whatever original cell I’m working with, and sometimes I notice that the ideas stemming from these original cells are vastly different. I’ve been trying to get away from writing music that sounds like it goes through a lot of disparate things, though I really like long-form pieces that have a lot of different sections — it seems to be my thing. Something that I always think about is how to make the transitions smooth, I spend a lot of time on transitions. I give a lot of thought to: “okay, if I want to have this in the piece, if this part is really important to me, but it sounds really different from the other parts, how do I make it so that it doesn’t come out of nowhere?” Even if the pieces are already cohesive to me it’s also important for them to be cohesive to the listener.

For instance, in your piece 1994, you have the first third of the tune, and then a section in the middle for piano with background lines, and those background lines lead into the last third of the piece. I thought that was a very seamless way to thread those together. Can you talk a little bit more about how you wrote that piece?

That piece was composed using morse code! I wrote all the music for Simple last summer (2013) — I spent three weeks by myself in Canada, on Bowen Island in British Columbia. The experience was great though maybe a little bit too isolating… Anyway, before I went, I had this idea before I went to write all the music for this new album using morse code. It was an interesting place to start, though I discarded it as my sole inspiration about a week in, as I found that it was tricky to come up with as much musical material as I thought I could. Or to put it another way, it seemed a little narrow to limit myself to that when there were some other avenues I wanted to explore as well.

For this piece, I developed a tone row using morse code: dot is a half step, dash is a whole step. I started on letter A and pitch A, so dot-dash (morse code for A) is a minor third; then B would be dash-dot-dot-dot, so that's a whole step then three half steps, a perfect fourth. And so I just went through the alphabet like that; this is a tone row of the alphabet. So then I put it all in one octave, which I didn’t like. So then I decided to check it out intervallically, and came up with some chords that I extracted from the row.

And then I decided to come up with a rhythmic component. So for every minor third it would be a bar of 3/8, for every perfect fourth it’d be four 8th notes, for every tritone it’d be 4:3, so on and so forth. So then I just took the intervals in this tone row and made it into a rhythmic row, and that’s the piece. The melody of the piece is literally just the notes of the tone row that I put into that rhythm.

Some of it is by ear too; using the tone row but going off of it a bit. Usually when I write a piece it’s not like “here’s a basic idea, and here’s the finished tune!” on the same page. But that’s how this one went, mostly. I had everything mathematically correct in the sketches and then changed it a little by ear, which I think is important to do if necessary.

Anna's Sketches:

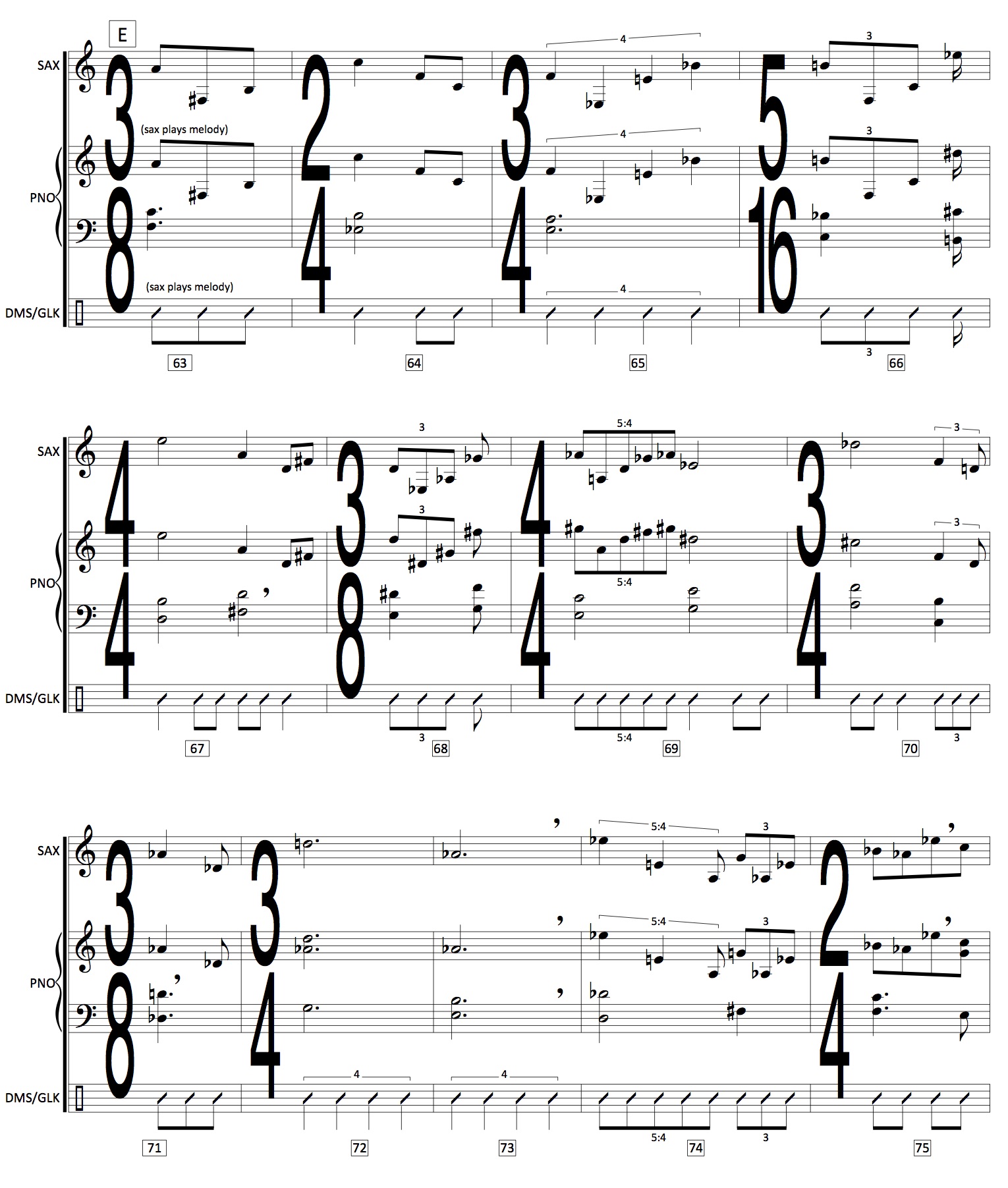

An excerpt from the finished score:

It’s funny you mentioned Tim Berne earlier. One of the things I brought to Bowen Island was the Bloodcount DVD. And this piece 1994 is pretty inspired by Tim Berne and from watching that DVD -- it was filmed in 1994.

It’s funny, Tim Berne’s language sometimes has that same sort of Webern-esque, pointillistic thing as 1994. But then this piece 1994 doesn’t sound like a Tim Berne composition to me.

From what I understand, Tim’s whole thing is that everything should happen differently every time, and that the compositions are there to make people improvise differently and the focus is on improvisation. For me, although of course I’m an improvisor and I love improvising, I kind of want the composition to be the focus. I guess that's a more controlling way to look at it, but that’s why I spend so much time writing the music! If I’ve spent that much time on it I really want it to happen the way I've set out. When I’m putting improvisation into my pieces, which is usually always, I tend to give people pretty strict directions about where and how I want it to go. And then I trust the people I hire to do my music to do whatever they want and fuck around with it, but I generally feel that improvisation should serve the composition. Or that's what I want for my music, at least.

When you’re in your precompositional stage — 1994 makes a lot of sense to hear it and feels very intuitive. Oftentimes these “rigorous” precompositional processes are maligned as being the opposite of something intuitive. I don’t buy that dichotomy and I don’t think your music has it on display. You’re also very clearly making concessions to your musical intuition as you go, as you said.

I think it’s pretty important for me to always try and listen as if I were just hearing the piece and not be so strict to the system. I tend to be very mathematical and heady when I write music, and I know that if I let that have its way then the music I write is shitty. I really need to use my ear. It tends to be super boxy otherwise; my compositions tend to be really sectional before I’ve edited them and made sure they sound like music.

So what was your experience playing this with Matt and John?

They fucking nailed it!

Hollenbeck probably took one casual look at it and went “Yeah, I got this.”

Well yeah, and you know, I was thinking of both of them when I was writing this music. I know their preferences and what they like and what they can do pretty well. This is totally Matt’s harmonic and rhythmic domain, I mean actually a much simpler version of it. Have you seen his scores? He’s really into complexity. I knew that he’d eat this up.

John and Matt are also just so busy and in such high demand, I’m kind of amazed we were even able to make the album in the first place logistically.

I like that the impulse not to find different musicians is becoming more common. I think there’s a shift away from the sort of “mercenary” jazz culture that was maybe more predominant a couple decades ago and back into a band idea, and I think the music benefits enormously from that mentality.

I do too. I think jazz is one of the situations where you’re playing original music and you’ll get someone who hasn’t played the music before to sit in on on a gig as a sub. I don’t hate it always, but how can you not prefer the original?

For sure. But then I guess there can be situations where it works fine, and can even be fascinating to see.

Definitely. It depends on the context.

You mentioned this music being a part of Matt Mitchell’s language. I wonder, have you thought much about this emerging aesthetic trend, these sort of modern/ultra-modern jazz + "new music" + prog + math rock worlds are all…there seems to be this new current, maybe especially in New York, where those genres are wellsprings for a new kind of post-genre world of improvised music. It seems like your music kind of falls into this, and maybe also Matt's music and the Claudia Quintet and plenty of other examples.

I don’t know. Yes, there are a lot of people who are writing music which blurs the lines between genres - Matt's music and John's music are definitely two good examples of that. Amongst my musicians friends, I feel like the prog + math rock + hip hop + jazz is much more common that people who are in to "new music" + jazz. My current preference is definitely for contemporary classical music. Sometimes it frustrates me that not a lot of my peers are into that - "new music" world has a lot of borders with the improvising world, sonically at least, and also has made a lot of advances in composition that many jazz musicians seem to be totally oblivious to! But all that being said, I think that the current trend in writing does seem to be stuff that falls in the cracks of genres - stuff that is classified as jazz only because of the presence of improvising.

I don’t have any productive insights about it either, it’s just an increasingly common thread I’ve been noticing here in NYC.

Sure. Also writing and practicing the hardest music we possibly can, a lot of my friends are into that. I did a duo set with my friend Patty Franceschy and we basically sight-read it on the gig and it was really challenging music. If I had looked at it five years ago I’d have thought "Holy Shit, that’s crazy." But it sort of seems to be the standard to write technically challenging music.